Jeff Liberty – Here and There

Films like “Lost in Translation” and “Up in the Air” give you the impression that business travel is a deeply lonely and alienating experience, especially for men. I can certainly understand how people who spend too much time on the road can feel disconnected from everyone and everything and exhausted from being nowhere and everywhere at the same time. When I travel for work, I do miss my family and the creature comforts of home. I can get tired of aggressively upbeat music in hotel lobbies and elevators, paranoia about the charge in my cell phone battery, and the endless search for healthy food and good coffee. At the same time, I’ve come to realize that traveling to new places for work sharpens my powers of observation and makes me feel more connected to strangers and, at some level, to my core beliefs and values.

Recently I visited San Francisco for a “thought leadership in education” event at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, which was half the reason why I was willing to travel across the country to attend. The gathering’s organizers had promised to “bring together 250 of the most interesting people” in the education space. Raised in a working-class neighborhood in Boston, it all seemed so pretentious, so self-involved to me. And yet there was a part of me that was flattered to be on this exclusive list and excited by the promise of a private, curated viewing of the SFMOMA’s Fisher Wing.

At Logan Airport, I was impressed by the young mothers who were traveling alone with young children and navigating strollers and diaper bags along with the normal amount of luggage through the security checkpoint. It struck me as particularly poignant that this generation of children—my own kids included—will grow up with the basic understanding that everyone is to some extent a threat and that no one can be assumed to be safe.

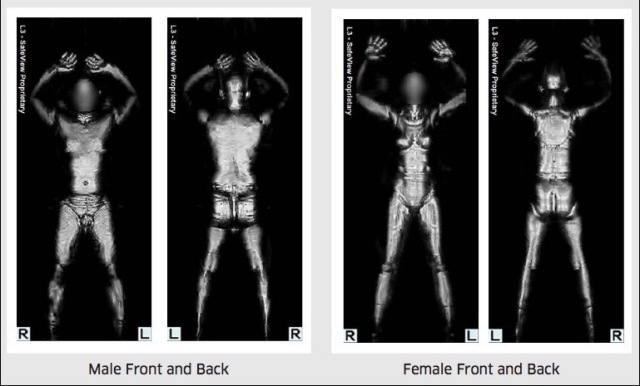

As I dutifully remove my shoes, suit coat, belt, and laptop and place them in gray plastic bins, I notice an African-American woman, her feet spread shoulder width and her hands raised above her head in the tubular full-body scanning machine. Her t-shirt reads “Free Black Woman,” and it occurs to me that no white person in America would ever feel the need to buy and wear such a shirt.

When it’s my turn in the body scanner, I mold my body into the pose required by the silhouette inside the tube and feel something like shame at the fact that, as a white man, my putting my hands up as I am scrutinized by paramilitary TSA agents must be a very different experience from the woman in the “Free Black Woman” t-shirt.

When it’s my turn in the body scanner, I mold my body into the pose required by the silhouette inside the tube and feel something like shame at the fact that, as a white man, my putting my hands up as I am scrutinized by paramilitary TSA agents must be a very different experience from the woman in the “Free Black Woman” t-shirt.

On the cross-country flight, internet access is spotty, which causes me some productivity-related angst, but the unreliable connectivity allows me to pay more attention to my fellow passengers, including a lovely older couple sitting next to me. I am taken by the easy way they ask each other questions and show genuine interest in responding to each other’s queries. At various points during the flight, they look up from their reading and share aloud long passages—the husband a whole paragraph from an article on Chinese currency manipulation from Foreign Affairs magazine; the wife a passage from People about the recent death of Mary Tyler Moore. Their tender regard for one another is apparent and makes me hopeful about the future of my own marriage over the long haul.

On the taxi ride from the airport, a gnawing feeling of nervousness starts to dog me. This is an old and familiar sensation of fraudulence I can sometimes feel when I am in social situations that feature lots of affluence. Most days I manage my emotions by reminding myself of my worthiness through positive self-talk, a concept that would have made my even more insecure teenage self want to punch my 47 year-old self in the face. On this day, however, I am having a hard time keeping my nerves in check, so I do what I often do on work trips—I go for a long walk.

On this crisp February morning, San Francisco strikes me as a symbol of everything that’s right and everything that’s wrong with America. Young San Franciscan professionals that I imagine to be employees of tech companies with edgy, ironic-sounding names commute to work. Nearly everyone has headphones tucked under fashionable hats and unnecessarily warm coats. Some talk to the wires next to their cheeks as they walk down the sidewalk. Others glance at their phones in between sips of coffee and tea as they wait for traffic lights to change.

This SOMA neighborhood is booming—there are new high-end construction projects on every block. Construction workers on their mid-morning breaks—burly, unshaven dudes in orange hard hats and yellow fluorescent vests—congregate in groups of three and four on street corners and on raised platforms made of dusty lumber and metal piping. They curse and smoke and eat slices of pizza and breakfast burritos and drink coffee from stainless steel thermoses.

On the same street as a futuristic hotel that looks like a series of glass cubes stacked asymmetrically, apartment maintenance workers power-wash shit-smeared sidewalks as city employees in cheery blue jackets remove cardboard boxes that have served as beds for the city’s many homeless residents the night before. Some newer commercial buildings feature sidewalks outside their windows in which large stones have been cemented into the walkway, ostensibly as a way to discourage people from sleeping there overnight.

I turn onto Mission Street. Every few blocks there are medical marijuana dispensaries with names like “Spark” and “Relief.” Their bouncers, muscular giants perched on too-small bar stools at the front door, check their phones and wait for trouble I hope will never come. I spot a young man passed out on the sidewalk, his back held upright by a temporary construction fence. Shafts of morning sun warm the lower half of his legs. An unlit cigarette balances impossibly, almost comically, from his mouth. One of his hands is open, palm outstretched to the heavens. A cell phone is clutched in his other hand. Thinking of Jacob Riis, I want so much to take a picture of this boy, whom I judge to be around twenty. I want to bear witness, to share his image with the wider world. Like the black woman at Logan, he seems to represent something potent and crystalline about the challenges and opportunities of the moment we’re in. I wonder if there is any way that I can frame the shot that will not strip him of his remaining dignity. Ultimately, I walk back in the direction of my hotel. On the way to my temporary home, I notice that the wall of the San Francisco Chronicle has a deep crack in its façade, where black Gothic letters teach me that the paper was founded in 1865—the last time we had Civil War, I can’t help thinking.

——————————————————————————————————————-

A few weeks later, I stop into the Backyard BBQ Pit in Durham, North Carolina. The snaking lunchtime line curls like a long sausage chain through the restaurant. Every skin tone and hairstyle in America seems to be represented and people of all ages are happy to wait for the fried whiting, the pulled pork sandwiches, the turkey plate, and the famous mac and cheese.

An older gentleman with a kind sun-splotched face and bushy eyebrows that can’t decide what direction they want to grow in enters the crowded shop. He moves slowly, almost painfully, with the help of a metal cane, uncertain about where he should place himself in the line. Two elderly black women allow him to cut in front of them. For a second, I consider offering to let him go ahead of me as well, but something about the interaction between the ladies and this man seems to me to be a deep but quiet gesture of Southern gentility, something subtle that a lanky Yankee in a suit like me can recognize but not fully comprehend.

The man slides into the space the ladies have created for him and clutches the wooden frame of a nearby booth for balance. He introduces himself to me as Chase. When I share with him that I’m in town for work, he tells me that his daughter is a teacher and his son-in-law is a youth minister. Chase tells me that he’s 80 years old and has survived five different kinds of cancer, one of which resulted in his liver being removed. As we wind our way through the restaurant, inching closer to the mouth-watering food that Yelp has promised, he tells me about his son who died at 48 of a heart attack while skiing.

“You can accept other kinds of death,” he tells me, his blue eyes suddenly far from this BBQ joint. “My parents, even friends. You expect that. But your own child,” he trails off. “That’s different.”

One of the chefs pops out from behind the counter, taking fried food orders that he seems to remember with ease without writing them down. The catfish comes so big that it can’t fit on the plate, Chase tells me. He asks me if I have children. He celebrates my choice of the brisket, collard greens, and squash. When the time comes to pay for my food, he shakes my hand with startling firmness, wishes me luck on my trip, tells me I’m doing good work, and shuffles off towards the door with two sandwiches, one for himself and one for his wife.

Having woken up early and having sat in the line for so long, I scarf down my lunch. The contrast of the tangy, spicy red vinegar with the moist brisket is divine. Chewing on a mouthful of bitter collard greens, I can’t help thinking about the fact that I’m only a year younger than Chase’s son when he passed away, the same age as my own father when he died when I was in college. I let two hush puppies dissolve on my tongue and wash them down with sugary tea, happy to finish the meal with a mouthful of sweetness before getting back on the road in my rental car.

Jeff Liberty is the Vice President of Personalized Learning at BetterLesson. Jeff has been married for 15 years and has two school-age children. A graduate of Emerson College’s MFA Program in Creative Writing, Jeff tries to get better at his use of words when he’s not trying to help teachers get better at their craft.